46 years later: The Marshall Plane Crash

On November 14, 1970, a plane carrying the Marshall University football team along with its coaches and a number of prominent fans crashed into a Wayne County, WV hillside just short of Tri-State Aiport. All 75 on board were killed in what, 46 years later, still stands as the worst sports-related disaster in American history.

I grew up in Kenova, WV just a few miles from where the crash occurred. I grew up a Marshall fan, going to games every weekend the Herd was at home with my father many times still in my own football uniform as we'd head to Joan C. Edwards stadium immediately following my youth league contests. We went to several away games as well including the 1999

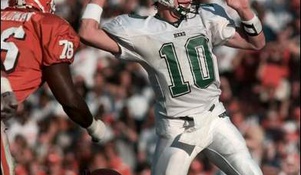

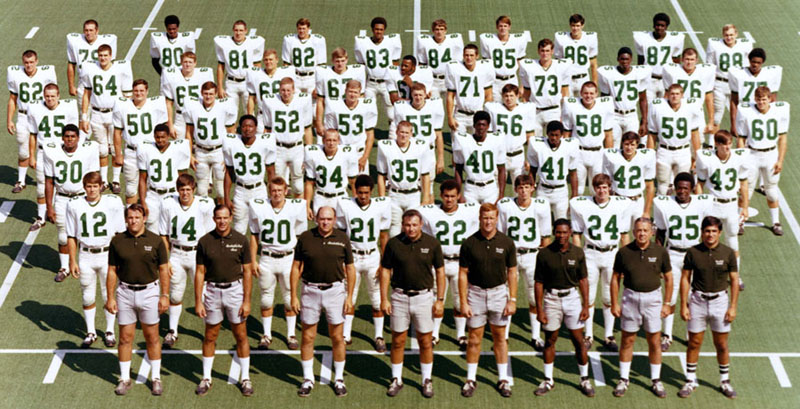

The Marshall football program that I grew up with was very different than the one my father had followed as a kid. The program I knew and loved was a dominating team that won more games than any other program during the 1990s, claimed two national titles at the D-1AA level and had almost effortlessly transitioned to a D-1A to continue its dominance in the Mid-American

I knew about the crash as a kid. I remember my Dad who was was just a month shy of his ninth birthday at the time the disaster happened telling me that the impact of the crashing plane shook his childhood home and sounded like a bomb had been dropped on the town. That minutes later sirens began to go off and for hours into the night they could still be heard as fire and

He did his best to make me understand that this was a seminal moment that had majorly influenced the Marshall, Huntington, and Tri-State that I knew and would continue to have influence well into the future. He tried to make sure I understood what such a loss of life meant and how fleeting life can truly be. Of course, I was a kid and while I understood the

I understood it a little better when I was a senior in high school. That was the year they were filming We Are Marshall and I drove to Huntington for

But, something about standing on the same campus in the same style clothes, reliving and re-enacting the same emotions and moments the people went through in 1970 really made the crash hit a bit deeper. However, it wasn't until the following year when I became a freshman at Marshall that it really sunk in just how significant the crash was.

I wrote for the MU Parthenon and did radio work for the school's

There are several memorials dedicated to the victims of that crash in Huntington and on campus. The student center where I spent much of my

"My hope is that it serves to commemorate life and living rather than death," Bertoia told reporters at the time. "That's why a fountain was chosen. Water is essential for life, so the waters of life that are rising, receding and surging from the fountain are to express upward growth, immortality, and eternality."

There is of course also the memorial at Spring Hill Cemetary where six members of the Marshall plane crash whose bodies couldn't be identified are buried in six unmarked graves. A large obelisk displays the names of the six players - James Adams, Mark Andrews, Michael Blake, Dennis Blevins, Willie

But, the most meaningful memorial to those lives lost is the program itself. Every fall when a new Marshall team takes the field they are honoring the 1970 team that never made it home from a

"All of these firetrucks and ambulances were speeding by the house," Hardin told me. "So I reckon I ought to follow them."

So he did and when he arrived on the scene the hillside was engulfed in flames and the smell of jet fuel and burnt foliage hung in the air.

"It was chaos," Hardin said. "At that time nobody knew it was the Marshall plane or if there was anyone still alive so all of the first responders are just scrambling."

It was Hardin who would help discover that it was indeed the Marshall plane. As he got out of his vehicle, stepped over the guard rail and began to navigate his way around and through downed trees and logs to the wreckage, something caught his eye.

"It was a piece of metal, a piece of the plane," Hardin said. "I picked it up and it had the letters ERN written on it. My first thought was eastern ends with ERN this must be an eastern flight. But, somebody said Jack, southern ends in ERN too."

At that moment Hardin and the others on the scene began to realize that the plane was likely the plane carrying the Marshall football team. Later, through items like wallets, that were found confirmed their suspicions. At that point, Hardin said he began to make his way back up the hillside to use a radio to contact the Herald-Advertiser's (Herald-Dispatch today) newsroom and tell them what was happening.

"As I was walking back I stepped over a log I had walked across on the way down," Hardin said. "Only this time the way the light from the fire hit it, I could actually see it better. That's when I realized it wasn't a log. It was a person. Believe me, when I tell you, this was the most devastating thing I had and have ever seen."

After the interview concluded I thanked Mr. Hardin for his time and shook his hand. He said to me then that he wasn't sure if modern Marshall teams understood how important they are to the people who experienced the crash first hand or people who were directly impacted by it.

I think the 2016 team provided some reassurance of that on Saturday night. Despite being ensured a losing record and despite rumors of dissension and locker-room problems Marshall took the field against Middle Tennessee State honoring both the 1970 team and the 1971 team with locked arms. It was a show of unity, of togetherness that hadn't been displayed by this Thundering Herd team all season. Marshall went on to hammer the Blue Raiders 42-17 in the team's best effort of the season.

They knew what was at stake and as a team, they were able to put everything else that had happened this season behind them, for at least one night, to achieve something greater than themselves. They didn't honor the 1970 or 1971 teams because they played in black jerseys with throwback decals on their helmets. They didn't even honor the 1970 or 1971 teams because they won the game. No, they honored them, because they played together, with great effort and great heart. They found something in themselves that they hadn't had all year long. They knew they had to because they knew an entire school and town, as well as 75, lost but not forgotten sons and daughters of Marshall counted on them to.