What you can learn about race in America from the story of Caron Butler.

Caron Butler was my favorite Wizard when I lived in DC between 2005-2009. $10 Student Wednesdays was the hook up! They gave us best seats available and the Wiz were solid then, too. The “pretty decent size three” of Caron, Antawn Jamison, and Gilbert Arenas led by Eddie Jordan's Princeton style offense consistently got the Wiz into the playoffs where they shared some truly memorable battles with the Bulls, and most notably, the young Lebron James and his Cavaliers.

Caron stayed out of the Arenas-style antics. Didn't get into Deshawn Stevenson-type, rapper-supported, discussions about who's overrated or not. Just went about his business. Tough as hell on the court, soft-spoken in interviews. By all accounts, a great chemistry guy in the locker room, and a no-nonsense type of dude. The type of athlete I admire. The exact type of player and person George Carl realized he needs for his Sacramento Kings - a very exciting and young squad, but one in which experience, composure, and leadership is scarce - as they have signed Butler to a two-year deal this summer.

This particular athlete, as I learned at some point while following the team, deserves one's admiration for more than just a uniquely smooth pull-up jumper after his trademark shake and bake. Not just for that signature one-handed hanging on the rim after a dunk, which he likes to do. Caron Butler has seen his share of shit in his life. Raised by a family with love, but supported by a well-established family business that reflected the sad realities and inevitable demand in the surrounding communities – drugs.

At some point during watching a Wizards game, I learned that Caron, the proud product of Racine, Wisconsin had been locked up 15 times by the time he was 15 years old. I later learned he was selling drugs at the age of 11. When you pause and think about it, the previous sentence should be absolutely shocking, but he talks about it calmly, almost with a sense of inevitability. The way he phrases it, during an episode of Vice Sports, which made me want to write this story, very clearly underlines how his environment made him want to dip into the world of crime and drugs. Money and lavish things were the obvious appeal, but the status was an additional factor. When his father and uncle would come back from prison they would be looked at as legends, Caron says. “I wanted that”, he continues as he smiles in reflection.

“I couldn't see past this block right here” Caron admits during his video for Unscripted. But on that block, amidst very limited perspectives, albeit illegally, Caron found a job, money, and a lifestyle. The all-too-familiar story of the young black man with potential. Surrounded by temptations, secluded from the mainstream world, the prospect of earning quick money on corners made much more sense for a young man than the out-dated, analog, world of unrewarded obedience that is public schooling. He later also found trouble and continuously landed himself in jail. This story is not limited to deep corners of the hood. Growing up attending some of Chicago's better public schools – both academically and in basketball – that story is ever so present. And it can end in many different ways. To illustrate my former proximity to such situations I recall, that, as teenagers, Jawaun Westbrook and I talked about playing professionally in Europe together. I have to admit, he was bad as hell – bad as in good on the court and just bad off it. But it was clear that if he stuck with it, his game could take him far. Last I heard his name was about a year ago when I read in the Trib that he had been arrested for assaulting a woman with a hammer by Chicago's Navy Pier. And yeah, Juwaun was an unruly kid, but as with literally everything in the race conversation you can look at it in two ways. Juwaun was a bad man destined for a bad future or he was a product of an impoverished community, a single-parent home, a failed system, and lack of role models. I happen to believe the latter.

Caron was also a product of similar conditions. As a result, he consistently landed himself in the penitentiary. And the first 14 times he found himself there, among people struggling to get out of the same life he was in, prison only reinforced his position in the game – gave him experience, reputation – definitely not reform. There is an insistence on punishing in the US that can legitimately be questioned in terms of its efficiency. The US incarcerates 25% of the world's prisoners despite being just 5% of the world's population – in raw numbers it translates to more incarcerated citizens than in the top 35 European countries combined. Yet, it also ranks high in crime nationwide, while the south side of Chicago can legitimately be called a war zone. Moreover, a disproportionate amount of those incarcerated citizens is African American even though that group only comprises about 13% of America's population. And thus, again, we can look at that in multiple ways. In America, black people are 6 times more likely to be murdered than white people and 8 times more likely to be murderers.

Many people believe that the above is because black people are more prone to committing crimes. Which to others is ludicrous as it is completely unsupported by empirical data. What is supported by science is the notion that a reality of systemic discrimination perpetuates a cycle of violence, drug use, and poverty. Moreover, that cycle is influenced by a clearly prejudiced law enforcement network. Consider the fact that black people are 3 times more likely to have their cars searched for drugs while it is the white people who are 4 and a half times more likely to have drugs in the car when they are stopped. In the words of a race and discrimination expert Tim Wise that is not only “stupid ass law enforcement” but also reflects a reality of prejudice among cops that results in a series of cases where cops recklessly harm or kill unarmed black people. And let me be abundantly clear about this – I do not label those individuals as overtly racist – they, too, are products of the omnipresent, silent racism, that subconsciously convinced white people that they are the normal ones, which makes them have to actually put in an effort to treat other ethnic groups with dignity. It shouldn't take effort to treat people as people, yet we've conditioned ourselves into such a situation.

What ends up happening is that cops, regardless of their race, have a skewed view of black people. To the point that when a black man like Levar Jones, gets pulled over for a seat belt violation at a gas station, walks out of his SUV (presumably already identified in the white cop's mind as potentially a drug dealer's vehicle), gets asked for a license and registration, reaches back inside to get them, and much to his bewilderment, gets shot multiple times in the legs. Because, of course, in the racist mind of that cop, he was reaching for a weapon.

Jones' story very clearly illustrates this dynamic, so I chose to use it, but thankfully it didn't end tragically. However, there is a plethora of cases to choose from if we're looking for tragedy. Of the ones you may remember from the news in recent months is Michael Brown, whose controversial shooting sparked riots in Ferguson and a discussion about police brutality nationwide. Or the case of Eric Garner, who was resisting his arrest for selling untaxed cigarettes and got choked to death by the police in broad-day light while pleading “I can't breathe”. While the story of Sandra Bland has many people realizing that a group of masked hackers is now more trustworthy than those sworn to “protect and serve.”

The individual stories are backed by statistics. According to the Guardian, “in the first 24 days of 2015, police in the US fatally shot more people than police did in England and Wales, combined, over the past 24 years.” In a separate study they conclude that black people are twice as likely to be shot when unarmed when white people, though that number I think is actually higher. Every week it seems, social media welcomes a new video of an unarmed black person getting shot by the police. The world of these realities, realizations of injustice, feelings of helplessness, and sheer fear caused by a justifiably perceived lack of protection from the structures, has led some members of the black community to identify Ghana as the most attractive place for them to relocate. Think about that.

The above environment unquestionably translates to a harsh reality. Caron's harsh reality got even more severe during his 15th trip to prison. He was serving a one year sentence and found himself in solitary confinement for an extended period of time. Ironically, one of the worst places for a man to find himself in, was the place where Caron found himself. The SHU was where Caron was able to be isolated from literally everybody for 23 and a half hours a day. He was able to see inside of himself and he felt a need for a change in his life. He saw who he was – which he describes in the most brutal of ways - “I just felt like I ain't shit” - he admits in interviews. He saw what he wanted to be. He would soon realize what he could become.

When Caron got out he was done. Done with that game and on to a brand new one. In prison he fell in love with basketball and quickly rose in the ranks of Wisconsin's best High School hoopers. Eventually earning himself a scholarship to a national powerhouse – UCONN. Butler balled out at Connecticut averaging 20.3 PPG and 7.5 RPG his sophomore year when UCONN won the Big East title but got bounced out of the tournament by the eventual champions, my Maryland Terrapins (sorry Caron). That year Butler's accolades included co-Big East Player of the Year and... an “All-American”. A hugely significant title for someone who had picked up his love for basketball during his 15th trip to jail. On to the league. Drafted 10th overall by the Heat, Butler put up solid numbers and built a steady reputation, making 2 All Star teams for the previously-mentioned Wizards along the way. Then capping his career off with a title in 2011 – standing on top of his profession – a champion – Caron Butler.

And it almost didn't happen.

On January 22nd 1998 – year and a half since Caron's stayed away from the drug game – when home alone, the police stormed into his house and conducted a raid. They found 15.3 grams of crack cocaine. Caron claimed it wasn't his, which was true, but he was the only person home, had plenty of priors, and didn't have much of an explanation other than his word that the drugs weren't his – open and shut case. Considering his history, Butler was looking at a minimum sentence of 10 years if convicted.

Richard Geller was the commanding officer during this raid. At one point he walked over to his deputy, leaned over and said “I don't think it's his”. The subordinate responded “if that's what you think, let him go.” So they un-cuffed him.

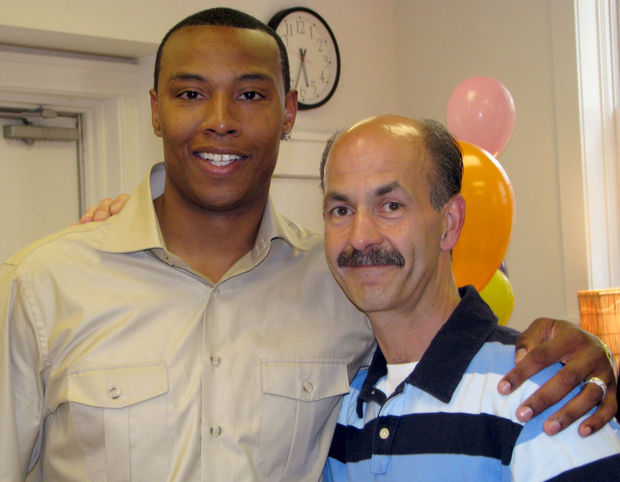

Let me be unequivocally clear – that never happens. We're reaching a point where the last thing on the minds of African Americans is getting some slack from the police, as they're more concerned about just staying safe and having their rights respected during a routine traffic stop. Some would say that Caron got lucky, but the truth is he didn't do anything wrong. Officer Geller merely did his job particularly well that day. An important part of the job of a police officer is discretion – the freedom to decide upon a course of action in a particular situation. He looked at Caron, he saw how he was affected by the present situation. He knew what a guilty man looked like and he knew he wasn't looking at one. In a very direct way he saved a career. In a more indirect way, through the resources that that career allowed Butler to raise, he's affected numerous lives through Caron's community and entrepreneurial work. The two have stayed in touch and they now run a charity organization called Cops'n'Kids together.

Caron's story shows very clearly the effects of his environment on the outcomes in his life. While surrounded by impoverished conditions and limited opportunities, Butler found himself living a life he wasn't proud of and didn't enjoy. But as soon as somebody gave him a shot, he flourished. Not just as a basketball player – he thrived as a community leader and a businessman – a true... “All-American”.

It takes two things for Caron Butler's story to be possible. An extraordinary individual – who is capable of taking a life lesson and truly applying it through strength of character, strong will, and perseverance. And a little faith from the world, a little luck, someone taking a chance on you. We can't live in a world where the mainstream only takes a chance on the white kids, while the ubiquitous prejudice and discrimination limits the possibilities of other groups. We can't live in a world where we talk about meritocracy but public schooling is funded by real estate taxes on a district level creating an obvious, but ignored perpetual cycle of maintaining or enlarging societal, educational, and income gaps. Change has to come in a multitude of ways, but one of those ways is to bring open and honest conversation to the forefront, face the facts, learn from empirical data, and adjust societies' perspectives on racism, race, discrimination, and bias. And we must do so both collectively and individually.

So next time you walk into a Burger King you'll see a bunch of people in hairnets and disposable gloves, working to make a living. Some will be immigrants, striving, often hopelessly, to find a better life. Most will be from impoverished communities - fringes of society – places that occasionally appear on television to evoke an altruistic response from you. Emotional porn designed to somehow make you feel like it's your fault that people are suffering because you haven't donated money. Most of the time, these places don't appear on TV at all however, while in pop culture they're depicted to be ghettos where minority groups run wild with guns and drugs, failing to consider the terrible flaws of all the systems around them. So when you're handed your Whopper try to refrain from judgments about those people. You don't need to fear them, look down on them, or think of them in any way as different at all. Put away the contempt and feelings of superiority. Consider that Caron Butler used to work at Burger King – he now owns six. All because he was given a chance.